[Donatello’s] work showed such excellent qualities of grace and design that it was considered nearer than was done by the ancient Greeks and Romans than that of any other artist …. He was superior not only to his contemporaries but even to the artists of our own time (Giorgio Vasari, Lives, 1568).

In keeping with this summer’s theme of sculpture at Dickinson, and our recently-concluded Renaissance sculpture exhibition, we turn our attention to one of the greats in the medium: Donatello. Together with the sculptor-architect Brunelleschi and the painter Masaccio, Donatello was a leading figure in the invention of the Renaissance style in the visual arts. His pre-eminence was recognised and celebrated in his own day, and his work remains prized today. Although artworks attributed to Donatello himself are exceptionally rare – the Quincy-Shaw Madonna of the Clouds in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is his only autograph relief in a United States public collection – his enduring influence can be seen, and admired, in the work of successive generations of artists.

(Left to right) Donatello, David, 1408-09, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence;

Donatello, St Mark, 1411-13, Orsanmichele, Florence

Donatello’s early recorded apprenticeship took place in the Florentine workshop of the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1404-07, while Ghiberti was engaged in designing the models for the famous bronze reliefs on the north doors of the Baptistry. The following year, the young artist was commissioned to sculpt figures for the niches on the cathedral façade, and a full-size marble statue of David (now Bargello, Florence), originally intended for the Cathedral but instead placed in the Palazzo della Signoria by the City Council. In 1411, Donatello was commissioned by the Linen Draper’s Guild to carve a St. Mark, the guild’s patron saint, for its niche on the Guildhall of Orsanmichele, and its success led to the 1417 commission from the Guild of Armourers for a statue of St. George, also for Orsanmichele. Beneath this figure, Donatello carved a marble panel depicting St. George and the Dragon, using a newly developed technique of extremely shallow relief – almost drawing on marble. The technique, known as rilievo schiacciato (literally ‘squashed relief’), was remarkable for its ability communicate recession in pictorial space without literal depth, and it became one of Donatello’s greatest contributions to Renaissance sculpture. The term itself was first recorded by Vasari, who praised Donatello when he wrote of reliefs ‘called flat and pressed [stiacciato or schiacciato] relief, which show nothing but the drawing of the figure in a pressed and flattened out elevation. They are very difficult to execute, because it requires great skill in disegno and inventione, and it is challenging to create gracefulness by contours alone. And in this genre too Donato [Donatello] worked better than any other sculptor, with arte, disegno and inventione.’

Donatello, St George, 1417, and the relief panel or ‘predella’ depicting

St George and the Dragon below, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

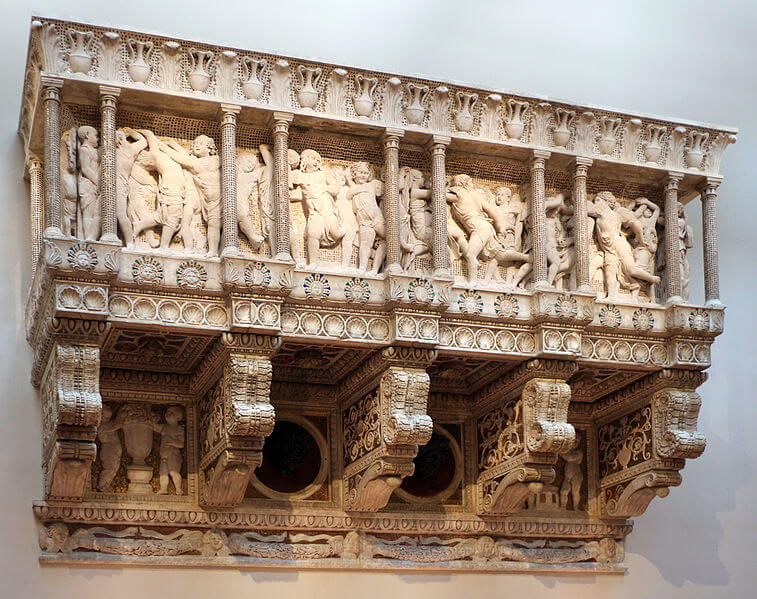

Donatello received the first of several commissions for the Siena Baptistry in 1423, for a bronze font relief; subsequent commissions included two bronze figures of Virtues (1428–9), a bronze tabernacle door (1429), and three bronze putti (1434). Beginning in 1425, Donatello shared a studio with the sculptor Michelozzo, and he continued to receive prestigious commissions in Florence. Projects included an elaborate marble cantoria for the Florence Cathedral (1433-39), and his celebrated bronze David (c. 1430-40), executed for a Medici patron; this represented the first free-standing male nude sculpture since Antiquity. When Donatello began work on his cantoria for the Duomo, the sculptor Luca della Robbia was at work on a similar project for a cantoria, and thus the two sculptors were working as neighbours. As a result of their contact, Della Robbia’s early terracotta roundel-type bust Portrait of a Youth (c. 1435-40) shows an awareness of Donatello both in the youthful, slightly androgynous physiognomy, with the simplified forms of the head and almond shaped eyes, and in the perspective, as it is designed to be placed high up on a wall and seen from below.

Donatello, Cantoria, 1433-39, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Donatello, David, c. 1430-40, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

In 1443, Donatello departed for Padua, where he remained for around a decade. His first commission in that city was for a life-size bronze Crucifix (1441-49) for the basilica of San Antonio, but his best known was the magnificent bronze monument to Erasmo da Narni, known as ‘Gattamelata’, captain-general of the Venetian army (1447-53). Modelled on the celebrated equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius statue in Rome, Donatello’s Gattamelata is the first freestanding bronze equestrian statue since antiquity.

(Left to right) Luca della Robbia, Portrait of a Youth, c. 1435-40, with Simon C. Dickinson Ltd;

Donatello, Equestrian Statue of Erasmo da Narni, known as ‘Gattamelata‘, 1453, Piazza del Santo, Padua

Donatello returned to Florence in the early 1450s, remaining there apart from a brief period in Siena, and his final decade was largely occupied by a project for the bronze narrative reliefs for the pulpits of San Lorenzo, assisted by his pupil Bertoldo who completed the commission after Donatello’s death in 1466. At the instruction of Cosimo de’ Medici, Donatello was buried in the crypt of San Lorenzo, the Medici family church, alongside his illustrious patrons.

Donatello, Penitent Magdalene, 1453-55, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

Donatello was remarkable as an artist for a number of reasons. He was adept and innovative in a wide range of materials, sculpting in marble and stone, terracotta, bronze, wood, and stucco, combining media and embellishing works in gilt and polychrome using the lessons of his early goldsmith’s training. He looked to Antiquity for inspiration, in turn inspiring successive generations with works such as the bronze David and the Gattamelata; he invented and popularised the rilievo schiacciato technique (rather than following the dominant relief style, which combined high and low relief); and his late, carved wooden masterpiece The Penitent Magdalene shocked viewers with its unflinching realism, in contrast to the standard iconography of a beautiful, graceful young Mary rather than a haggard and emaciated penitent.

Sculptures by, or even convincingly attributed to, Donatello are exceptionally rare on the market. Of the two offered at auction this century, a Virgin and Child in painted terracotta relief sold for $5,641,000 (against an estimate of $2-4 million) in 2008, while a terracotta Madonna and Child (the so-called Borromeo Madonna) fetched $4,440,000 (against an estimate of $4-6 million) in 2006; the latter is now in the collection of the Kimbell Museum where it carries the designation ‘Attributed to Donatello’. We can, however, appreciate the legacy of Donatello in artworks currently or recently on the market.

Pietro Paolo Olivieri, The Creation of Eve, c. 1580, with Simon C. Dickinson Ltd

Among those working in rilievo schiacciato after Donatello were Desiderio da Settignano, Mino da Fiesole, the brothers Antonio and Bernardo Rossellino and Agostino di Duccio. Michelangelo experimented with the technique early in his career, carving the Madonna of the Stairs in 1491, when he was just 16. In 16th Century Tuscany, Leonardo’s nephew Pierino da Vinci was carving superb low reliefs in white marble, while in Perugia, Vincenzo Danti was also inspired by Donatello’s relief sculptures. In the late 16th Century, the Roman artist Pietro Paolo Olivieri carved The Creation of Eve (c. 1580) – which was at one time attributed to Pierino – filling his composition with decorative vegetation and lively animals. Scholar Lorenzo Principi compares The Creation of Eve relief to the work of a goldsmith, and although we don’t know anything about Olivieri’s early apprenticeships, he may have had training similar to that of Donatello.

(Left to right) Workshop of Donatello, Nativity, mid-15th Century, Sold by Simon C. Dickinson Ltd;

Donatello, The Piot Madonna, 1440s-60s, Musée du Louvre, Paris

As a result of the wide-ranging appeal of Donatello’s compositions, some of the most popular exist in numerous versions. Such is the case with a mid-15th-Century polychrome and gilt stucco Nativity, attributed to the workshop of Donatello and sold last year by Dickinson. The work is closely related to a bas relief in terracotta, with inlays of wax medallions, of the Virgin adoring the Christ Child, known as The Piot Madonna (Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Donatello himself. Several versions of this extended relief are known, each of them with slight variations in design and finish, suggestive of specific commissions from a major workshop. In the relief sold by Dickinson, the scene has been extended to include Joseph and animals and the composition has been fitted into an arched shape, better suited to a more complex scene.

Attributed to Benedetto da Rovezzano and Donato Benti,

Saint Sebastian, c. 1503-04, with Simon C. Dickinson Ltd

Donatello’s influence can also be seen in freestanding sculptures such as a Saint Sebastian, carved in white marble and attributed to Benedetto da Rovezzano and Donato Benti (c. 1503-04). We note in particular in the saint’s slender, youthful figure and graceful contrapposto, which recall those of the bronze David. Donatello’s bronze David was one of the most influential sculptures of the Renaissance: having been commissioned by a member of the Medici family for the courtyard of a palazzo, it stood next in Florence’s Palazzo della Signoria before being moved to the Palazzo Pitti (17th century), the Uffizi gallery (1777) and then to the Museo del Bargello (1865). It has been widely copied in bronze and plaster cast, as well as in marble.