Collectors are always on the lookout for artworks that represent good value as well as good quality. One collecting area in which we believe this can be found is Modern and Contemporary Latin American art and our continuing strong sales in this sector certainly support this view. If you’re considering an addition to your collection, and Latin American art is an area you might like to explore, here are some of the names you should look out for.

The Uruguayan-Spanish artist Joaquín Torres-Garcia (1874 – 1949) developed the Neo-Plastic grid structure of his Paris years to support his particular Latin American abstract language, Universal Constructivism. Into this austere geometry, arranged according to the ratios of the Golden Section, he introduced a pictographic language derived, at least theoretically, from enigmatic Pre-Columbian inscriptions.

J. Torres-Garcia, Grafismo universal sobre plano de color, 1943, oil on paperboard

1950 marked the rise of Geometric Abstraction in Brazilian art, a trend resistant to the Abstract Expressionism that dominated North American art at the time. It occupied Brazil’s artists for nearly two decades, and saw the emergence of Hélio Oiticica (1937 – 1980), a leading figure in the field of Arte Concreta (Concrete Art). Oiticica produced corpus that continues to fascinate scholars and collectors for its conceptual inventiveness, socio-political engagement, and visual pull.

H. Oiticica, Grupo Frente no. 10, 1957, gouache on cardboard. Sold by Dickinson to a private collector

The Cuban artist Wifredo Lam (1902 – 1982) contributed to modernism as a painter, printmaker, sculptor and ceramist. He explored the possibilities of Cubism and expanded the inventive parameters of Surrealism, while negotiating figuration and abstraction with an extraordinary imagination. Between 1923 and 1940, Lam lived and studied in Madrid, but with the outbreak of the Second World War he fled home to Cuba. There, Lam explored a newfound interest in Afro-Caribbean culture and spiritual traditions such as Santería, traditions from which he had deliberately distanced himself during his time in Europe. In his figures from this period, with their fusion of human, animal and plant-like elements, Lam was responding simultaneously to European modernism and to the artistic heritage of Havana.

W. Lam, L’Oiseau blanc, 1968, oil on canvas. Sold by Dickinson to a private collector

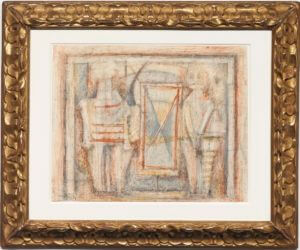

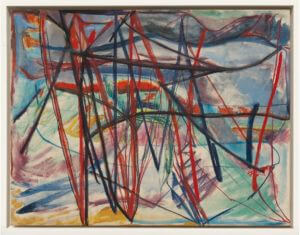

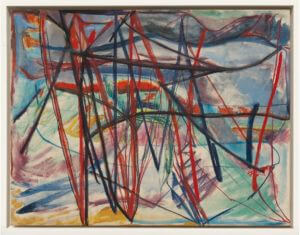

Rufino Tamayo (1899 – 1991) moved from his native Mexico to New York in the late 1920s, and then to Paris in 1949, taking his inspiration from the European modernism he encountered – mainly Cubism and Surrealism. In works like Dos Figuras, he synthesises these influences with native elements such as a rectangular motif that could represent a painting hanging on the wall, a shield from a Pre-Columbian civilization or an hourglass representing the passage of time.

R. Tamayo, Dos Figuras, 1962, pastel and pencil on paper. Sold by Dickinson to a private collector

In recent years collectors have also turned their attention specifically to works by Latin American women artists, recognising this as an area of particularly good value. At Dickinson we have championed these artists for a number of years and believe their work to be undervalued even now. Very few of them are household names – perhaps only Frida Kahlo – while many more offer tempting opportunities for collectors. In an effort to shine a spotlight on this sector of the market, Dickinson is dedicating its 2021 Frieze Masters stand to works by Latin American women.

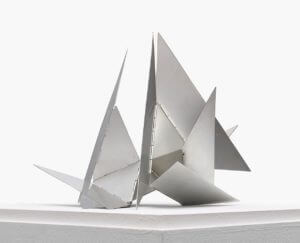

Two Brazilians, Lygia Clark (1920 – 1988) and Lygia Pape (1927 – 2004), were important contributors to the Neo-Concrete movement, a splinter group of Brazilian Concrete Art defined by more sensuous colour and greater poetry. Lygia Clark moved to Paris in 1950 where she studied under Isaac Dobrinsky, Fernand Léger and Arpad Szenes for the next two years, before returning to her home in Rio de Janeiro. There, she transitioned swiftly from conventional painting to gestural abstraction, and helped to usher in the Neo-Concrete movement. From 1959 into the 1960s Clark made a series of geometric, hinged aluminium sculptures she titled Bichos, Portuguese for ‘creatures’, explaining: ‘I gave the name Bichos to my works of this period, because their characteristics are fundamentally organic. Furthermore the hinge between the planes reminds me of a backbone.’

L. Clark, Bicho Desfolhado, 1960, aluminium, in sixteen elements. Sold by Dickinson to a private collector

Lygia Pape, meanwhile, was politically active, but her work was rooted in poetry rather than ideology. In many instances, her varied and expressive style anticipated works by more famous names: for instance, in 1957, Pape created a series of prints of squared incised with thin stripes resembling pin-stripe suiting. The resemblance of these works to Frank Stella’s iconic black paintings is undeniable – but Stella’s series was inaugurated two years later, and thus it may have been Pape influencing Stella rather than the other way around.

María Freire (1917 – 2015) was a painter, sculptor and critic who became a leading figure in the development of Concrete and non-figurative art in her native Uruguay. Much like the Cubists in Western Europe, Freire was drawn to the stylised features and flat forms of African masks, also finding inspiration in Pre-Columbian art. In 1953, Freire visited the 2nd São Paulo Bienal where she was introduced to the work of Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and Friedrich Vordemberg-Gildewart, among others. This was followed in 1957 by a trip to Europe – including visits to both the Stedelijk and Louvre museums – which gave Freire additional exposure to current developments in European abstraction.

As Fascist persecution escalated in Italy in the 1930s, Mira Schendel (1919 – 1988), who was of Jewish descent, fled to Yugoslavia and ultimately left Europe for Brazil in 1953. Although her work was informed by the Neo-Concretists, Schendel never officially joined the Neo-Concrete group nor the subsequent Tropicalia cultural movement, due in part to her work’s resistance to easy categorisation. Recurring themes include letters, geometric figures and phrases reflecting a radical lexicon, often juxtaposing elements from two languages (visual and numerical). Many of her compositions hover in the space between drawing and writing, creating a certain visual poetry.

In the 21st century, Cuban-born Carmen Herrera (b. 1915) carries the torch for the Latin-American avant-garde. Thwarted for years following her return from Paris to New York in 1939 – ‘a Cuban? a woman?….They wouldn’t look at your work’ – Herrera found recognition very late in her career. Today the doyenne of geometric abstraction, she has claimed her place within the history of Post-War painting, her work featured in major museum collections and celebrated in an acclaimed retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016.

C. Herrera, Sin título (Habana #35), 1950-51, acrylic on canvas. Available for sale at Dickinson